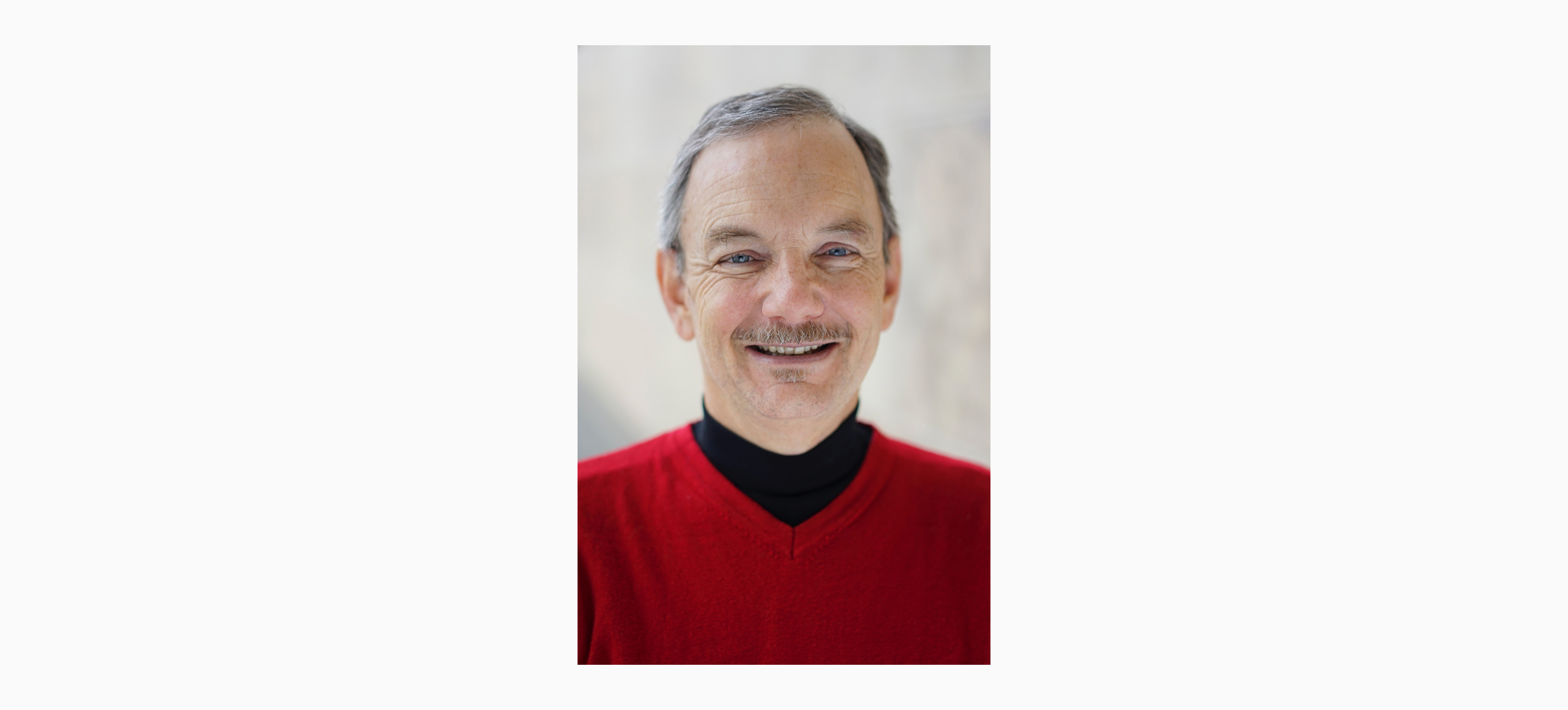

Understanding Local Sales Tax: An Interview with Mike Bailey

Mike Bailey has worked in local government finance since 1980. Mike was a finance consultant with the Municipal Research & Consulting Center (MRSC) and has been the Finance & Technology Director for the cities of Redmond, Renton, Lynnwood, Everett, and Wenatchee. He is a former president of the Washington Finance Officers Association (WFOA) and served on the Government Finance Officers Association’s (GFOA) Executive Board. He was chair of the GFOA Budget and Management Committee and is the local government representative to the Streamlined Sales Tax Project. Mike is a CPA, and his BA and MBA are from the University of Puget Sound. He conducts workshops on local government financial management, budget, and financial leadership and leads council retreats and strategic planning processes.

Russ: Understanding the history of local sales and use taxes should help sellers appreciate why we have the complexities we do in this area. Sales taxes were widely adopted by the states in the 1930’s, and applied almost exclusively to physical goods, usually bought locally, and often just around the corner. What is bought and how it is bought has changed a great deal since then, but those systems are still largely in place. How would you characterize the role of sales tax for local governments as the states adopted these taxes.

Mike: Local governments are “creatures”; of the states – that is to say that they are created by each state through that state’s laws (and constitutions in many cases). As such, they are subject to the limitations and privileges characterized by that state’s laws. One of those privileges is the ability to raise revenues to carry out their missions. A common source of revenue has been the taxes on sales that occur within their jurisdictions. Since the state limits the types of revenues a local government can utilize, a sales (and related use) tax can be a very significant source of this revenue. Some states have granted a great deal of local control over these revenues (often referred to as “home rule”;) wherein the local legislative authority (a town or city council, a county commission or a special purpose district board) can act fairly independently of the state in the administration of their affairs. Local governments take these responsibilities very seriously and work to protect this autonomy vigorously.

While local governments can have a wide variety of responsibilities, all general governments (that is, those that are not formed for a unique or special purpose – such as a utility district or transit district) have many responsibilities that do not generate related revenues. For example, there are no revenues (at least no sufficient revenues) derived from public safety activities, transportation system maintenance, land-use planning activities or general government functions (such as legislative or executive responsibilities). These activities rely on what is commonly known as “general revenues”;, or those that can be used for any legal governmental purpose. The sales tax falls into this category. As a result, the internal competition for access to these scarce revenues can be significant. General revenues include property taxes, sales (and use) taxes, business taxes and some fees (many fees are dedicated to being used for the service that the fee is related to). Again, competition for these general revenues is often the crux of many local government budget debates.

Russ: How many states depend on local sales tax revenues to fund municipal operations? For how many is it a, if not the, major source of local funding?

Mike: Local sales taxes are one of the major pillars of funding for local governments across the country. The sales taxes typically are clearly delineated as “local”; in the majority of states. In some states, local sales tax remains an important source of funds though it is collected as a single state tax and then distributed to local governments as state aid based on a formula of some type (population, assessed value, etc.).

Russ: Why is local sales tax so important in the states that have it? What are the government services local sales tax most commonly funds?

Mike: Local governments tend to have a few primary sources of general revenues (that is revenue not dedicated to a specific purpose). One of these is the local sales tax. In some states, the local general government tax structure results in sales taxes as the largest local revenue source. Ideally local governments have a “multi-legged”; stool of local revenues. This enables more stability in the local revenue structure that many rely on as the economies evolve.

Examples of the types of services that fall into this general government category include public safety, transportation systems (road, bridges, street-signs, sidewalks), land-use planning, parks (and often recreation), etc. Essentially all cities, counties, towns and villages across the country have some type of retail-based tax to help pay for these types of community needs. (In some cases, these revenues are collected solely by the state, but then the state passes them through in various forms.)

Some special purpose districts have added sales taxes to their revenue profile recently as well. Examples of this includes transit systems, economic development districts and cultural districts. In some cases, the logic is that those who visit or use these systems can contribute to their development and upkeep by shopping in the regions that are bolstered by their existence. The theory is that as a government invests in a revitalization program, the business activity will bring new shoppers in to spend money, support the business and help pay for the improvements as well.

Russ: The rapid increase in internet sales had an adverse impact on many main street retailers, especially in smaller and rural communities. How would you describe what happened?

Mike: The economy has changed significantly over time. This change began prior to the pandemic as technology enabled remote commerce to occur on an expanded scale. The transition from traditional “brick and mortar”; sales to remote sales evolved from a mail order catalog to the internet. With the onset of the pandemic, many physical retail locations closed. Most local governments anticipated a significant decrease in retail activity and the related local sales tax revenues. This was certainly true of the physical retail sales. The shift to remote commerce surprised many. While local governments were initially concerned that dramatic reductions in sales tax revenues would force budget cuts, the expansion of remote sales taxes provided welcome stability to local budgets.

Russ: Those main street retailers who survived had to adapt. Some of them have thrived. What things have they done that allowed them to continue, and in many cases, grow?

Mike: We are now seeing local brick and mortar retailers recognize that the shift to remote, internet-based sales could jeopardize their business models. Some are working to develop an online presence while others are partnering with marketplace-based systems to extend their reach into the remote sales space.

Russ: What opportunities is the internet providing for new retailers at the local level? How are they different from traditional main street retailers?

Mike: While the internet offers opportunities for local retailers to expand their markets, they must also seek ways to differentiate themselves from the large, low-cost internet-based retailers as well. Some are pairing their wares with services to address this issue while others are looking to fill niches not easily addressed by larger retailers. In addition, many customers still value the instant gratification of walking out of a store with their purchase. As a result, having inventory on-hand can also be a differentiator.

Russ: When local sales tax revenues don’t come in where projected, where do state and local governments most commonly turn to get the revenues they need?

Mike: Part of the answer to this question stems from another common element in local, general government revenues – the property tax. Property taxes are another significant source of local government revenues. However, most states impose limits on the rates of growth on property taxes. As a result local governments have come to rely more heavily on sales taxes as well as fees and charges. You may have seen this in your local community. When sales taxes don’t meet the need, or are less than anticipated, local governments don’t have many alternatives for quickly responding to the resulting budget challenge.

Russ: When local sales tax revenues don’t come in where projected what kinds of services get cut?

Mike: You’ll note I’ve used the phrase “general government revenues”; in these discussions. Local governments have a variety of functions (utilities, parks, public safety, roads, transportation systems, etc.) Sales taxes are one of the revenue sources available for those needs that don’t have a dedicated revenue source. These typically fund public safety, general transportation systems, general government (such as land-planning, development permitting, legislative and management systems), social services parks and recreation

Russ: Besides city and county sales taxes, there are a myriad of special purpose districts that depend on local sales tax revenues. What are some of the largest, smallest, most common, and most unusual kinds of special purpose districts?

Mike: Sales taxes are part of the mix of revenues used for a variety of special purpose needs. Examples include public transportation, special purpose facilities (such as sports stadiums) and other public amenities where the theory is that the publicly provided amenity generates economic activity which in turn generates the sales taxes used to provide for the amenity itself (think tourism related taxes used to fund stadiums or convention facilities).

Russ: Projected local sales tax revenues often form the basis for other kinds of project financing. Increment tax financing comes to mind. How does that work, and how does that help local communities?

Mike: Across the country there are different approaches to tax increment financing. This mechanism anticipates that a public project will create in increase in economic activity – an increment. The taxes on the increment can be used to pay for the underlying project. In many cases, these taxes are either property or sales taxes. Once the project financing term is complete, the incremental increase in taxes can then revert to the underlying government to pay for more traditional services. It is common for the tax increment applied to the project to be a percentage of the total collected. So, the state and local governments begin to benefit from the project immediately and will eventually be able to realize all the related revenues for their non-project related purposes.

Russ: Local governments were critical in getting the Streamlined Sales Tax Project, and later, Governing Board, off the ground. SST put some restrictions on how local sales taxes could be structured and administered. Why did many local governments nonetheless find it important to support this effort? (Hoping to get authority to collect on internet sales?)

Mike: There were different perspectives on the benefits and risks related to the Streamlined Sales Tax Project (SSTP) from a local government perspective. Realizing that this effort started well before internet-based sales taxes were a significant part of the of the retail economy, some local governments thought that changes being discussed and implemented by the SSTP represented more risks than rewards. Many local governments had invested heavily in creating a local economy based on physical retail sales. Such features as auto malls, large shopping centers and warehousing / distribution centers were parts of this approach. These sales were based on the physical presence of the transaction within their borders.

Only after evaluating the quickly changing landscape of retail sales did local governments see the potential for a new retail sales tax scheme, one based on where the retail goods are delivered. While this did not address some aspects (such as warehousing), it was soon clear that even automobile sales could be conducted remotely. This significantly changed the sales tax landscape and the related economic development equations related to it.

Lastly, I’ll point to one of the benefits that I’ve worked to champion as part of the SSTP. I believe that we should do whatever we can to make it easy for businesses and individuals to comply with the laws and regulations we place on them. The SSTP has partnered with the business community to gain their perspectives and insights. This has helped those of us in government to have a better understanding of their concerns and issues.

Russ: How has technology proved a boon to collecting local sales tax revenues?

Mike: Along with improvements in the ability to conduct sales using technology, the ability to administer the registration of businesses and collect related taxes or fees has dramatically improved. Again, this should enable those of us in government to find ways to lower the burden of tax collection. It will also provide for better data and insights into economic activity. This will help in revenue forecasting, understanding economic swings and other dynamics where a proactive government might be able to prove helpful.

Russ: How can retailers take advantage of technological advancements to meet their tax obligations?

Mike: Innovation in retail models has also resulted in innovation in tax collection systems. For example, a small retail operation can join forces with a large marketplace vendor and leverage their marketing, markets and tax administration capabilities. They can also utilize systems between their “point of sale”; systems and a tax schema that lowers the compliance barrier for tax collection. The SSTP has worked to support the development of these systems almost from the beginning of their work. The “certified service providers”; (CSPs) were merely a concept when the project started exploring ways they might be able to assist with lowering the burden of tax administration and collection. They are now a thriving part of the remote sales tax administration landscape providing technology solutions to a wide variety of businesses.

Russ: Some local jurisdictions are perceived as being difficult – in the sense that they seem resistant to modernization and simplifications. Local jurisdictions sometimes question allocation of revenues over tiny amounts. Is that an accurate perception? If so, what do you think is behind this?

Mike: As I said previously, some local governments have spent years developing a local economy based on physical retail sales. In many cases, this approach has served these governments very well. It is difficult for those local governments to envision walking away from those investments.

In addition, these environments have relied on physical transactions (again, think auto sales, large malls, etc.) The sales tax schemes in these cases are also typically “origin based”; – that is the tax gets credited to the local government where the sale originated. The transition to a “destination based”; scheme (where the sale is credited to the locality where the goods will be delivered) undermines these investments as well.

The transition to a remote sales economy is a struggle for many in local government to embrace if it means undermining their years of effort for a strong local economy. However, as more sales move to a remote mode, this transition is occurring. In Washington State we found ways to bridge this transition. We’ve been working to help others make this same journey and standardize retail sales commerce across the country.

Russ: In some states there has been a lack of trust between local jurisdictions and state legislatures and administrators. Have you seen this turned around anywhere? What advice would you have for these groups to improve their working relationships with each other? Are there some examples where state and local government cooperation works especially well?

Mike: The perspectives on these issues are often territorial. Each level of government has to balance its own budgets. This means that they can become focused on maximizing the revenue to their government. States often administer a sales tax, along with the local sales tax. States can also administer their sales taxes while local governments administer their taxes. In either case the opportunity to combine efforts and improve the efficiency of both is overlooked because of this focus on our own budgets and related revenues. This can complicate issues for business as well!

While this dynamic continues to exist, I have seen improvements. For example, here in Washington State a new director for the state department of revenue saw the benefits of improved partnerships. She created a liaison position for local governments and hosted open forums to share information and improve working relationships. It was during this improved period of cooperation that we were able to revise the local sourcing from “origin”; to “destination”; dramatically improving our conformance to other states. It is my hope that we’ll see the benefits of improved cooperation, especially as it creates the potential for lowering the burden of complying with tax laws for business.

Russ: Is there a role for the business community in fostering this cooperation?

Mike: Yes, as an integral part of the larger equation, business must be involved. Again, I think the best systems result of cooperation and the best systems will benefit business.

Russ: What do you think are the most important reforms local jurisdictions can undertake to make life easier for taxpayers, both their own taxpayers and those collecting from internet sales? And why should they care about out of state sellers?

Mike: The cooperation we’ve discussed can extend to the local marketplaces as well. While I was a finance director for a Seattle suburb I worked with our local elected officials, the business community and tax administrators. We explained that we wanted to improve the business climate as the nature of business changes. We listened to the retailers and offered to assist them as best we could. We also directed them to resources in this regard as well.

As commerce continues to change governments must adapt. We will do this best by interacting with those closest to the change.

Russ: Are there reforms states can undertake to make life easier for local jurisdictions without making life more difficult for taxpayers?

Mike: Yes, I think the example I’ve described above is a good one. Working together can be challenging, especially if we see others in the equation as having differing goals than our own. The long history of the Streamlined Sales Tax Project included many hours of government and business working together towards common goals – but from different perspectives. The success of the project can be an example that this approach works and should be extended to others who are not yet been involved in these discussions.